Can sustainability be saved by tackling loneliness, not just CO₂ emissions?

Raz Godelnik is an Associate Professor of Strategic Design and Management at Parsons School of Design — The New School. He is the author of Rethinking Corporate Sustainability in the Era of Climate Crisis. You can follow him on LinkedIn.

Can sustainability be saved by tackling loneliness, not just CO₂ emissions?

Earlier this month, I stopped at Sunshine Coffee in Laramie, Wyoming, on our way to Yellowstone Park. What brought me there was the fact that it’s a zero-waste coffee shop, with no single-use consumer items. In other words, there are no disposable cups — not for customers dining in, and not even for those who want their coffee to go, like I did. Instead, you can either bring your own reusable cup or get your drink in a glass jar for $1, which is refunded on your next order when you return it (or you can simply keep it, as I did).

At first, I was excited about the zero-waste coffee shop concept, wondering what it would take for Starbucks and other coffee chains to adopt it and eliminate the waste that has become an integral part of our coffee (and other drinks) consumption. But as I waited for my coffee, I began to notice something else — something that had little to do with waste and everything to do with people.

As I looked around, I noticed their stickers. Beneath the logo, it read: Zero waste. Community space. Suddenly it clicked — this coffee shop isn’t just about eliminating waste; it’s about creating a place where people feel connected. As owner and founder of Sunshine Coffee, Megan Johnson, explained in an interview with This is Laramie: “I wanted to bring sustainable values to Wyoming as well as build a business that serves the community.” That got me thinking about how the second part — serving the community — is integral to the first. After all, in a world where loneliness — a key barrier to people’s well-being — is on the rise, shouldn’t creating spaces for connection be just as central to sustainability as going zero waste?

Photo: Sunshine Coffee

Then, while drinking my coffee on the road, I thought about the kind of value sustainability creates for people. In most cases, this value is framed mainly around environmental impacts — in this case, eliminating waste. While many people care about that, it’s rarely enough on its own, as shown by the struggles of many sustainable products and services to scale. On the whole, people don’t see enough value in environmentally driven offerings to justify any downsides they may have — such as a premium price — and fully integrate them into their lifestyles. As a result, most companies lack a strong demand-side incentive to act more boldly on sustainability.

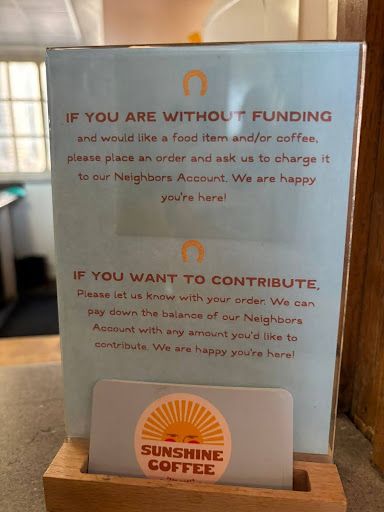

At the same time, as Sunshine Coffee shows, sustainability can create clear and meaningful social value. For its customers, that might mean a sense of connection and belonging to a community — for example, through its Neighborhood Account, which offers food and drinks at no charge to those in need. Anyone can contribute to the fund, supporting community members facing food insecurity. The result is a tangible expression of care that fosters belonging and mutual support. As one reviewer put it: “This is my go-to place for early meetups, community events, and coffee! I love that it’s in a neighborhood and that I bump into so many people I know here. The zero waste is such a huge benefit!”

As such, this kind of space speaks to more than just meeting material needs — it addresses a pain point many people experience: loneliness.

Defined by Feng and Astell-Burt as “a felt deprivation of connection, companionship, and camaraderie,” loneliness affects at least a quarter of adults, “and the consequences can be deeply damaging to mental and physical health.” Addressing it taps into a need that is personal, emotional, and immediate — exactly the kind of value that could strengthen demand for sustainability solutions. Why? Because currently much of the value created by sustainability solutions is detached from people’s priorities and immediate concerns, making them less likely to resonate and easier to attack by ‘predatory delay’ actors benefiting from the status quo.

Sustainability must connect with people and deliver tangible benefits. The reality is that its current value proposition is, for the most part, too weak to move people at scale toward low-carbon lifestyles. In a previous article, I argued that companies should focus on the customer case for sustainability, using the jobs-to-be-done framework to identify what matters to their customers and where sustainable solutions can address real problems.

For example, for most people, disposable coffee cups or packaging are minor inconveniences at best. We might recycle when we can and move on without much thought — hence why Starbucks’ model still thrives. The same certainly holds for invisible benefits like reduced carbon emissions: people may care, but not enough for it to outweigh convenience, cost, or habit.

When environmental value feels remote and sustainable options come with trade-offs — from higher prices to more effort (e.g., refillable packaging) — sustainability stays weak. Making it strong requires redesigning solutions to build in benefits people truly value and design out the frictions that hold them back.

This is why addressing loneliness can provide a critical added value for companies to consider when designing sustainable solutions. Connecting these solutions to urgent social needs like loneliness — alongside their environmental benefits — can make sustainability products and services far more relevant and appealing to people’s everyday life. It can even help overcome the hurdles of the trade-offs involved in switching to sustainable alternatives, i.e. I may feel more comfortable paying more for a coffee in a coffee shop, providing me not only with zero-waste experience, but also with a sense of community.

If sustainability is to resonate, it probably needs to touch not just ecological impacts but people’s lives — starting with the pain points they feel most. Addressing loneliness, for example, can provide a critical added value for companies to consider when designing sustainable solutions. Connecting these solutions to urgent social needs like loneliness — alongside their environmental benefits — can make sustainable products and services far more relevant and appealing to people’s everyday life. It can even help overcome the hurdles of trade-offs involved in switching to sustainable alternatives. I may, for instance, feel more comfortable paying more for a coffee if the café offers not only a zero-waste experience, but also a genuine sense of community.

Thus, I couldn’t help but wonder: Could scaling sustainability solutions depend on pairing “zero loneliness” with zero-waste and other environmental goals like net-zero?

You might wonder whether adding yet another goal to an already full plate is the right move for corporate sustainability. Wouldn’t making sustainability even broader work against making it more appealing to the public? Does it really need to be stretched further to succeed — or should we just focus on making it affordable?

Let me start with the last question. It’s not an either/or choice but an and one. The dominance of economic concerns suggests a greater need to make sustainable solutions affordable. This should be a top priority for any company working on sustainable innovation. But that doesn’t mean they shouldn’t also find ways to add value by addressing loneliness. In fact, for companies struggling with affordability, adding value that matters to people can help justify higher prices — as in my earlier coffee example.

As for the question of adding more to the sustainability plate: it’s not about piling unnecessary weight onto the sustainability agenda, but about adding value people actually care about. For example, with all due respect to companies’ efforts toward the SDGs, most customers are unlikely to see these efforts as relevant to their lives or as reasons to purchase sustainable offerings. This doesn’t mean companies should stop these efforts (though not necessarily through the SDG framework, which I find ineffective), but they should strive for greater resonance with customers. Here, helping address loneliness could be a powerful lever. Ultimately, it’s about creating more value for customers — which, in turn, translates into more value captured by companies.

So, what can companies do about loneliness?

First, addressing loneliness is a growing market opportunity, so businesses should view it not only as a sustainability concern but as a strategic business opportunity. That said, some responses seem less appropriate — ranging from AI “virtual companions” to real companions rented by the hour. The kinds of responses worth pursuing are those that genuinely bring people together, countering the deprivation of connection, companionship, and camaraderie. These can operate at many levels, from direct initiatives to more systemic approaches that address what Prof. Xiaoqi Feng calls ”lonelygenic environments” — complex contextual conditions that can cause or worsen loneliness.

So, what specifically can companies do, specifically in the context of their sustainability efforts about loneliness?

The third space — one option is to create or support spaces for socialization. Sociologist Ray Oldenburg coined the term “third spaces” to describe “informal spots to gather outside of home and work for socializing.” These can include coffee shops (though not Starbucks, which has tried but whose corporate nature and generic vibe as a global chain prevents it from truly serving this role), libraries, gyms, dog parks, playgrounds, and more. In the sustainability realm, repair cafés, community gardens, and farmers markets are good examples. Some may point to virtual groups — like Buy Nothing Facebook groups — but I agree with Oldenburg that third spaces need to be physical, not virtual, to genuinely foster community and human connection.

Companies can determine which type of third space best aligns with their products, services, and customers — and then build on it, either by supporting an existing space or creating a new one that strengthens the perceived sustainability value of their offerings. For example, an outdoor gear brand could support local climbing gyms or hiking meetups, a food company might host community cooking workshops, and a tech firm could sponsor repair cafés or makerspaces (yes, Apple, I’m looking at you). IKEA could offer carpentry lessons in local community centers, while fashion companies might organize clothes swap parties. Companies could also sponsor the equivalent of spaces like The Jar in Boston, which build on the power of art and culture to foster relationships, in other communities.

The key is how companies frame these efforts, as this is not about philanthropy but a strategic extension of their sustainability commitments. Companies that treat it merely as philanthropy will fail to create added value, while those that approach it strategically could unlock new engagement opportunities around sustainability. Their goal should be to make the third space a platform for connection while reinforcing the company’s broader sustainability vision.

Furthermore, companies can extend efforts beyond a specific “third place” into the broader notion of “third life,” weaving this notion of social and communal sphere of belonging and connection that people cultivate outside of home and work into their business models. For example, fashion companies that offer peer-to-peer rental options, banks that operate financial literacy centers to teach people how to better manage money and build wealth responsibly, or food companies that create neighborhood cooking clubs focused on healthy, sustainable meals.

You might think it sounds strange — or even far-fetched — that companies, transactional by nature and typically focused on profit-driven relationships, would take such steps or show genuine interest in supporting these kinds of initiatives. And not as philanthropy, but as part of their core strategy. It may also feel off to involve companies in activities rooted in community and civic life. Maybe — but then again, maybe not. Is it really so far-fetched to reimagine sustainability efforts in a way that actually meets people where they are?

For me, this goes to the heart of the current failure of sustainability in business: the narrowing of sustainability into a net-zero journey, no matter how little resonance it creates with customers. We’ve dug ourselves deeper and deeper into a framework aimed at driving change that most people don’t see, understand, or relate to. Addressing loneliness offers a way out — a proposition to shift toward a different type of sustainability, one that might actually work.

16 years ago, in his book Strategy for Sustainability: A Business Manifesto, Adam Werbach argued that a green strategy is not a strategy for sustainability. He called for a broader conceptualization — one that goes beyond a green product line. “An environmental goal is not enough to manage a company’s future successfully,” he wrote. Werbach emphasized the need to structure sustainability around a synthesis of environmental, social, economic, and cultural dimensions. That vision may now seem long forgotten in an era fixated on net-zero targets and the quest for the perfect reporting platform to back them up. But given the shortcomings of this approach, if not its outright failure, maybe it’s time to revisit Werbach’s idea — and consider how fostering a true sense of community could open a new pathway to success.

Link to original post can be found

here.

About the Author:

Raz Godelnik

Associate Professor of Strategic Design and Management

Parsons School of Design — The New School

PHOTO: Sunshine Coffee in Laramie, Wyoming

Read perspectives from the ISSP blog